Whitepaper: THE 5-STAR MODEL FOR TRANSPARENT ALGORITHMS

By: the 5 star community

Version: 1.0 (dated 06 December 2024)

Or download the PDF: Whitepaper 5-star model.pdf

From black boxes to transparent algorithms

Summary: Transparency is a core requirement for responsible deployment of algorithms by governments, but it is not yet sufficiently realised. There seems to be a lack of clarity, a hesitation to act, insufficient knowledge and risk-averse behaviour among government organisations when it comes to transparency about algorithms. Our research has revealed that the definition of transparency needs to be made concrete, manageable and secure in practice. We therefore introduce the 5-star model: a framework for step-by-step realisation of transparency. In this white paper, we tell you all about the need for transparency, the challenges government institutions currently face regarding transparency and the solution this model offers by demonstrating the content and application of the model.

1. The need for transparency

The use of algorithms by governments is not transparent, resulting in societal harm

The Netherlands Court of Audit concluded in its 2021 report Understanding Algorithms1 that the quality and risks of the use of algorithms by governments are insufficiently monitored. In their most recent study, the Court of Audit even states that the risks associated with the use of algorithms by governments are often underestimated. For more than a third of the participating organisations, it is unclear whether the deployed system is performing properly at all.2

This leads to concerns in society. According to the 2023 Algorithm Trust Monitor, trust in algorithms in the government has declined in recent years, with half of the population indicating that they think ‘executive organisations are not honest and transparent about the use of algorithms’.3 Combined with new legislation from the European Union, such as the AI Act, this puts great pressure on the government to provide more transparency about its use of algorithms.

Transparency - in the context of algorithms - is strongly embedded as a principle or requirement in legislation, policies, guidelines and frameworks.4 These documents seem to suggest that transparency is some kind of moral or societal endpoint. But it is crucial to see transparency not as an end goal, but as a means to achieve higher goals. For instance, the government should always be able to explain how decisions or policies are made. If it uses an algorithm to make decisions or policies, for instance by (partially) automating the process, making calculations or making predictions, then it must also be able to map out and explain this algorithmic process. Only then can the government be held accountable for the way tasks are carried out and can public supervision of quality and justice become possible.5 This makes transparency an essential condition for a properly functioning democracy.

A good step was taken at the end of 2022 with the launch of the Algorithm Register of the Dutch government. Government organisations can publish information about their algorithms in this Register.6 Thanks in part to the efforts surrounding the Algorithm Register, government organisations have started working on improving transparency. Yet the value of information included in the register is often still limited and insufficient to give different target groups real insight into the impact and operation of algorithms. For instance, results of impact assessments are rarely available and hardly any references are made to available source code. As a result, it remains unclear whether algorithms work properly and are deployed equitably in processes. Moreover, the vast majority of algorithms with direct impact on society are not yet in the register.7 Therefore, additional action is needed to make algorithms in the Netherlands more transparent.

2. The challenges

We engaged with professionals inside and outside the government to explore where the challenges lie within government organisations regarding algorithms and the transparency about them. According to this exploration, the challenges can be divided into roughly three categories:

-

Lack of clarity and hesitation to act when translating transparency into practice;

-

Insufficient knowledge and control over algorithms within the organisation;

-

Risk-averse behaviour when it comes to transparency.

We explain these challenges in more detail below.

2.1 Lack of clarity and hesitation to act when translating transparency into practice;

Policy and legislation pay a lot of attention to transparency and openness as a principle when deploying algorithms. The challenge is to translate these often generic provisions into concrete, implementable measures. The elaboration of transparency at the policy level is mostly theoretical and abstract. As a result it does not offer a clear view of what transparency means within the practical context of algorithms. About what exactly should transparency or openness be offered? Which target group should it be aimed at and with what end result? This creates a gap between policy and implementation. This is a well-known, difficult challenge for governments which, incidentally, is not limited to transparency in the context of algorithms.8 Yet it is particularly distressing in the context of algorithms, as transparency is a core requirement to prevent harm to citizens and society.

There is also a lot of ambiguity about the allocation of roles and responsibilities within the organisation. People want to do the right thing. This is certainly also true for government professionals working to improve the (information) position of citizens vis-à-vis the government. But there is currently insufficient clarity on what the rules, guidelines and obligations are for organisations, what vision on transparency should be followed, who within those organisations is responsible for what tasks, or what working methods should be used. There is also a lack of direction and ownership on this topic, which makes organisations wait and see. In practice, this leads to hesitation to act on transparency.

2.2 Insufficient knowledge and control over algorithms within the organisation

Currently, the information position of public organisations themselves with regard to their own algorithms is worryingly poor. This is due to a lack of knowledge and understanding of algorithms. This is problematic because without that insight, the government cannot improve the information position of citizens either. Smaller government organisations in particular lack the resources, people, time and money to invest in, for example, AI literacy and setting up processes to publish algorithms.

On top of that, there is a 'silo structure' within the government. That is: different teams, departments, domains and organisational layers function as islands and there is a huge lack of horizontal and vertical connection. Innovation with algorithms and/or AI is complex and often not addressed in an integrated way, making it very difficult for organisations to keep a grip on what is happening internally. Administrators are often not subject matter experts, but have to deal with complex, impactful decisions that require subject matter expertise, while subject matter experts are usually not at the policy table to give their input. This makes the threshold for administrators to realise transparency about algorithms in practice incredibly high.

Moreover, governments often rely on the expertise of third-party suppliers to procure and develop technology. Those suppliers are not always willing to provide transparency and openness about their systems to citizens (for example, for business reasons). Although attention to transparency about procured systems seems to be gaining traction among both developers and governments, hard agreements have often not yet been made. For instance, the Association of Dutch Municipalities' procurement terms and conditions (GIBIT) only mention that suppliers should be able to explain how the algorithm came to a certain decision, but the algorithm itself is simply regarded as the supplier's trade secret.9 This indicates a dependence on suppliers and a lack of agreements to include transparency from the very beginning in procured systems. Yet for responsible algorithm policy and for safeguarding our public values when deploying algorithms, it is essential that there is transparency across the entire ‘supply chain’ and life cycle of a system.10

2.3 Risk-averse behaviour when it comes to transparency

Driven by the prevailing mantra of digitalisation, data-driven work, and the hype around algorithms, there is a so-called 'technology push' within the government: the idea that innovation must take place in order to avoid falling behind. That technological opportunities must be seized to cut costs and increase efficiency. This often ignores the question of whether technology is the best solution to the problem at all and whether the impact on society can justify the choice of technology. As a result, there is an excessive focus on data, technology or quantifiable results when addressing challenges. While good solutions to societal challenges often lie in more participatory, social or human approaches that cannot be easily quantified. The dramatic consequences of this have become visible in, for example, the childcare benefits scandal at the Tax Administration and other examples of government organisations that have recently received negative press because of the application of harmful risk- or fraud-prediction systems.11,12

Partly due to this negative publicity, there is a strong focus on risk avoidance from the perspective of the government itself, rather than thinking from a human rights perspective and the interests of society. This creates a culture that is not conducive to upholding public values such as transparency and openness. Note: the cause of this culture lies not only with government organizations and their employees. The political atmosphere and the media also play a significant role in this.

At the same time, the national government and regulatory bodies (such as the Netherlands Court of Audit,13 TNO,14 the Dutch Data Protection Authority,15 the Council of State,[^]16 and the Netherlands Institute for Human Rights17) are increasingly emphasising and pushing for the mandatory publication of algorithms, the conducting of impact assessments, and putting the citizen at the center.18 Transparency plays a crucial role here, as how can one exercise oversight if there is no transparency?

This dynamic creates a culture in which the risk of 'transparency washing' lurks: giving the impression of being transparent while consciously choosing to share information that is 'safe,' rather than what is most meaningful or insightful. For example, by only publishing the 'simplest' or least impactful algorithms, or by intentionally keeping descriptions (such as in the Algorithm Register) superficial. This does not contribute to the ultimate goals of transparency, such as being able to account for, explain, or discuss decisions based on algorithms. Publishing 'something' in the Algorithm Register is not enough if it does not lead to meaningful insights for society.

3. The information needs from society

In addition to the conversations with professionals inside and outside the government, Open State Foundation and The Green Land organised a citizens' panel in 2024 for people interested in algorithms, but who do not necessarily know much about them. We spoke with them about what they would like to know about the algorithms used by the government. After all, they are the primary stakeholders when it comes to the use of algorithms by governments.

In the conversation with the participants, it became clear that the use of algorithms by the government raises concerns about the lack of 'human scale' in the execution of government tasks (also because people seem to be aware that generalizing automation is risky for those who fall outside 'the norm'). People find it important that, ultimately, a human carefully reviews the decision and takes responsibility for it. The possibility to choose an 'opt-out' is also appreciated: that there is (in some situations) an alternative to a digital or algorithmic process. Regarding transparency about algorithms, it was found that:

• It is important for people to know that a (partly) automated decision is made about them, what decision has been made, and which data the system used to support that decision;

• People do not necessarily need to know all the (technical) details of an algorithmic system, but they do need to be confident that the system is ethical and safe. A statement on this from (external) experts who have researched it can be help. When asked who should do this verification, it was found that the preference goes to an external party, who with an (interdisciplinary) team ensures that different perspectives from society are included.

• People do believe it is important for society to be more actively involved in decisions regarding the development or use of algorithms by government organisations.

It also turns out that the need for information can be very different for each person, situation or algorithm. The need for information is much lower for less impactful algorithms in particular, than when it comes to, for example, whether or not to grant a benefit. And more technically savvy people do need the technical details or source code, for example, so they can really investigate for themselves how an algorithm works. While that does not add value for everyone.

4. Our solution: the 5-star model

A framework for realising transparency step-by-step

Our research has shown that providing transparency and openness around the use of algorithms is highly desired by society. For the government, however, this can only be realised when it is made concrete, manageable and safe for organisations. Implementing it in practice is very difficult, only because transparency is currently still seen too much as an end goal. Without a higher goal for which transparency is needed, certain questions cannot be answered, such as for whom, on what issues, what level of transparency is appropriate or enough in different situations. This has caused a gap between policy and implementation, which - despite pressure from above - makes implementing transparency very difficult in practice. So the solution lies in providing clarity and practicability to those responsible for putting transparency into practice.

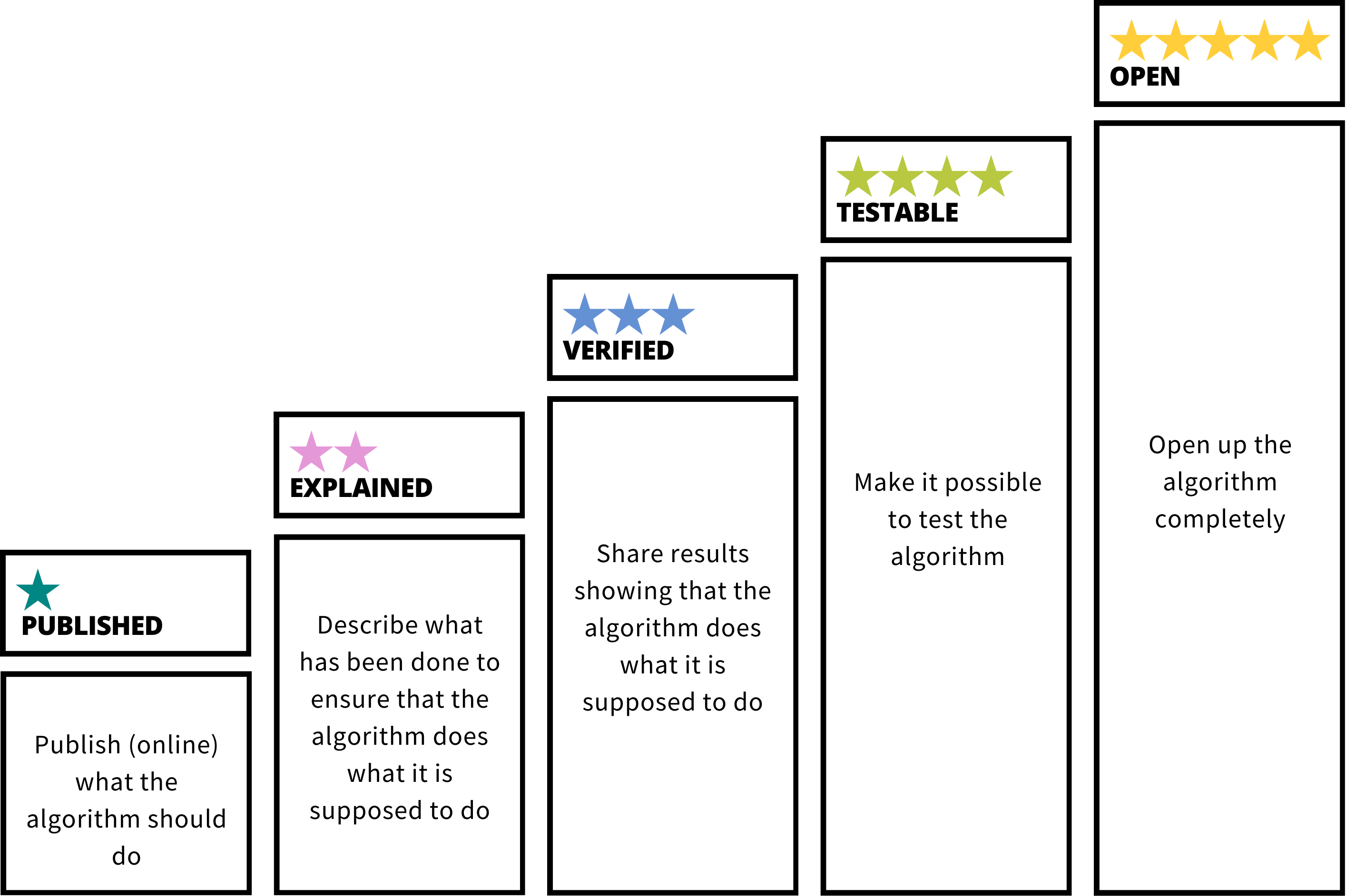

Interviews with experts and practitioners show that a gradation or stratification in the degree of transparency is useful in this regard. This makes it possible to set concrete ‘targets’ to steer towards, making it easier to implement. Layering also allows you to make meaningful choices about what information you offer to whom and when you do so. As a solution, we therefore introduce a step-by-step framework for transparency: the 5-star model for transparent algorithms (see Figure 1).

The 5-star model is a tool where, star-by-star, you increase transparency about an algorithm. With each star, you increasingly offer citizens the opportunity to see and judge for themselves whether an algorithm is being used responsibly. This starts with publishing information to let people know that an algorithm is being used and what it is being used for (Published). Then the algorithm is further described (Explained) and shown to have been thoroughly tested (Verified). To let people really form their own picture of how the algorithm works, people can experiment with inputs and outputs (Testable) or work through the full source code (Open). A more detailed explanation of these steps is given below.

Figure 1: The 5-star model consists of the stars Published, Explained, Verified, Testable and Open.

Figure 1: The 5-star model consists of the stars Published, Explained, Verified, Testable and Open.

4.1 Explanation of the 5 stars

It is important to view the 5-star model not as a checklist or an exhaustive overview, but as a tool to reflect on which information is valuable to share. This may vary depending on the specific algorithm.

1 ★ PUBLISHED

‘Publish (online) what the algorithm is supposed to do’

The first star is achieved when information about the algorithm and its application is publicly available, for instance, in the Algorithm Register. This means a description of the general characteristics of the algorithm is provided, which at minimum includes:

- A description of the purpose/function of the algorithm;

- A description of the role of the algorithm in relation to the process in which it is used;

- A (reasoned and explained) classification of the algorithm's impact.

With this information, you are transparent about the fact that an algorithm is being used, why and for what purpose it is implemented, and how impactful the algorithm is.

At this stage, it is also important to consider whether, and if so, how and when someone should be informed about the use of this algorithm. For example, in the case of a chatbot, it should be immediately clear to users that they are interacting with a bot. Additionally, references to extra information can be provided in the Algorithm Register. If the algorithm is used in a decision-making process, a link to this publication could, for instance, be included with the final decision.

2 ★ EXPLAINED

"Describe what has been done to ensure the algorithm does what it is supposed to do"

At this level, an explanation is provided on how the algorithm works and how it has been assured that it functions properly. This may include, for example, the following components:

- A description of how the algorithm works, for example through a flowchart showing the input and output throughout the process and the (calculation) rules applied;

- A description of the data the algorithm uses, or on which it has been trained;

- A description of the model's accuracy and how bias is dealt with;

- What measures have been taken to mitigate (societal) risks;

- Who or which parties are responsible for monitoring or maintenance.

The first point can be explained in general, but when applicable, it is also important to be able to explain it at an individual level. As was shown in the citizen panel, people want to understand the information (input) that led to a decision (output). For example, at the level of individual citizens, a file could be kept of decisions where an algorithm was applied, including an overview of which data was used, what output it led to, and why that output justifies the decision. This gives citizens the opportunity to understand the process and verify if the data is correct.

3 ★ VERIFIED

"Share results that prove the algorithm does what it is supposed to do"

At this level, not only is described what has been done to assure the algorithm does what it is supposed to do, but this can also be demonstrated. Results are shared that prove the algorithm works "well" and "fairly." This can be demonstrated, for example, by sharing:

- Audit results;

- Monitoring data;

- Results of ethical assessments (e.g., from an ethical committee or an fundamental rights impact assessment)

- How the algorithm was tested and validated, and what the results were;

- Other results from the "checks and balances" that are part of the life cycle.19

Among experts, this level was often mentioned as the minimum transparency level that a government algorithm should have. The importance of an (externally) audited and validated algorithm also emerged as essential for building citizens' trust in the government during the citizen panel (October 2024).

Sometimes, due to privacy or security concerns, not all aspects of an (internal) audit can be shared. However, this is not an excuse for never being able to achieve 3 stars — it is not an ‘all or nothing’ transparency. Results from assessments can be anonymised or summarised in a public version. The most important thing is to show how the algorithm was tested, what was included, what the outcomes were, and what measures or next steps were taken based on those results. Demonstrating a controlled operation helps build external trust in the functioning and application of an algorithm.

4 ★ TESTABLE

‘Make it possible to test the algorithm’.

At this level, stakeholders can start testing the algorithm themselves. People can then see for themselves what output is delivered with what input. This can be achieved, for example, with:

- An API with which results can be requested;

- A ‘mock-up’ system;

- Test data, possibly ‘synthetic’ (not the actual sensitive data but a comparable neutral set).20

This makes the algorithm and its operation tangible and thus testable. This is a prerequisite for having an open conversation about why the algorithm arrives at certain outcomes, whether these outcomes are desirable, and (therefore) whether the application of the algorithm in a specific process is responsible and justified.

Thoroughly testing an algorithm requires technical knowledge. This level is therefore more focused on experts who want to conduct research on the algorithm or possible biases. However, it is also conceivable to allow citizens to experiment with an algorithm in an accessible way. For example, by enabling them to see what outcome they get when entering certain data into a simple system or website. This is similar to online tools that can provide an estimate of whether you are entitled to a social benefit21 or how likely your certificate of conduct application22 is to succeed.

5 ★ OPEN

"Make (the development of) the algorithm fully open"

At this level, the algorithm is fully open. The code, data, control measures, and design choices are completely transparent, of course, in a way that does not compromise the privacy of those involved or create unsafe situations. The maximum openness is intended to allow experts or oversight bodies the opportunity to fully understand the algorithm. Specifically, this can be achieved, for example, by:

- Making the source code available in combination with contextual information, such as a "model card";23

- Making (training/test) data available;

- Choosing an open, participatory process in the development and application of the algorithm to ensure diverse perspectives are included.

This level may not be fully achievable for every algorithm. There can be many different reasons for this. However, even if complete openness is not possible, certain elements of this level can still be feasible and implemented. The more transparency and openness around an algorithm, the greater the contribution to rendering decision-making processes used by government organisations more accountable. Additionally, it can foster innovation and even provide suggestions or improvements to the code. This is also in line with the open-source policy within the Dutch government.24 Furthermore, the citizen panel revealed that involving citizens (whether experts or not) in the development of algorithms increases trust.

4.2 Purpose of the model

The 5-star model is intended as a guiding tool for all organisations, particularly public organisations, that work with algorithms and therefore need to take steps toward providing transparency about them. The model helps to articulate ambitions and goals regarding transparency, facilitate internal discussions on the topic, and raise awareness. Additionally, it provides guidance on how to implement these ambitions. The 5-star model is thus a tool aimed at 1) helping decision-makers and leaders articulate their ambitions for transparent algorithms, and 2) providing clarity on how transparency can be achieved in practice. The ultimate goal is that society has sufficient insight to understand, trust, or challenge algorithms and the decisions based on them when necessary. After all, transparency is not an end in itself!

5. Tips for Getting Started with the Model

Want to get started with the 5-star model but don’t know where to begin? The following steps can help you get underway with the model:

- Have discussions about what transparency means within your organisation and what is possible, taking into account the specific practical context and core values of your organisation.

- Make agreements (at the governance level) about the ambition level you aim to achieve for the organisation. For example: "We want to achieve at least 3 stars for all algorithms!" This provides a common goal and can create urgency to allocate time and resources.

-

Then, you can start mapping out:

-

The algorithms your organisation uses, develops, or purchases;

-

Who to approach for information about an algorithm;

-

What agreements are in place with suppliers and developers regarding the purpose, functionality, and explainability of algorithms;

-

The possible assessments that algorithms have undergone or will undergo.

-

With this information in mind, you can work step by step towards publishing algorithms. Don’t forget: perfectionism is the enemy of progress. So, just get started!

Finally, we have a few important considerations for the development and deployment of algorithms.

Adopt the motto: open, unless... In general, government organisations are always bound by legal (and societal) obligations to explain what they do and why. So, you could also ask yourself whether you should use an algorithm as part of your decision-making if you cannot or are not allowed to explain it. However, people will point out that not every algorithm can achieve five stars. This is a valid point, especially when privacy or national security is at stake. The highest achievable level of ambition should always be considered in context. When full transparency cannot be provided, organisations should not be penalised immediately, as long as there is a well-founded justification for it. Transparency can, however, be provided within these justifications.

Look before you leap Transparency begins at the outset, because without the right procurement conditions, providing transparency later on becomes difficult. Therefore, take this into account for future projects when procuring technology, so that you maintain control over your processes, can make good choices, and be accountable for them.

Align with the AI Act The European AI Act also prescribes what needs to be done regarding transparency. The first provisions of this law—concerning AI systems with an unacceptable risk—will come into force in February 2025. In August 2025, the provisions for "general-purpose AI models" will become mandatory. The government, at all administrative levels, must comply with the obligations of the AI Act. This creates urgency, as the topic must be addressed. While some organizations are already working on aligning with the AI Act, for many other entities, it is not yet a pressing matter. Above all, there is a lack of governance, leadership, and ownership in its implementation.

Don’t wait, invest now Understanding the algorithms used in your organisation’s processes is essential for delivering meaningful transparency in practice. Therefore, invest in knowledge, skills, and awareness within your organisation. By allocating resources and creating space to map out the algorithms together, you can gain much better control over your processes. Starting now will only make it easier to stay on track in the future. Providing transparency about algorithms isn’t a one-time task you can check off; it requires keeping the information up to date throughout the entire lifecycle of an algorithm.

6. Conclusion and call to action!

The 5-star model is designed to articulate organisational ambitions, facilitate dialogue, and foster urgency and awareness. Additionally, it provides practical tools to make these ambitions actionable. With this approach, we aim to lower barriers and enhance the ability to take meaningful action.

Managed by an open community, with Open State Foundation as ambassador

The 5-star model is an ongoing project developed and managed by an open and diverse community. In our view, everyone is a stakeholder, whether they are aware of it or not. Anyone interested is welcome to contribute and is strongly encouraged to do so. There is no supervisory or certifying body awarding the stars; organisations are free to use the model as they see fit. We warmly invite all organisations to adopt and work with the model! Don’t hesitate to involve society in the process, by gathering input or testing whether a given explanation is meaningful. Leveraging the community enhances public trust in your organisation and ensures expertise, diversity, and inclusion are embedded in your approach.

As a committed and experienced civil organisation in the field of transparency and openness in government, Open State Foundation assumes the role of ambassador for the 5-star model. This means they will leverage their expertise and network to promote and activate the model. However, they cannot do this alone. Therefore, we call on everyone to contribute to the following tasks:

- Participate (think, develop, and discuss)!

- Spread the word: Ambassadors at all levels—boardrooms, universities, secretarial meetings, editorial offices, around the copy machines, in the pub—are essential to spark a movement.

- Pilot cases: Do you work at an organization willing to adopt the model? Feel free to use it, share your insights, and ask for help when needed!

- Nay-sayers, have your say! We actively invite critical perspectives to challenge us and propose how it should be done.

Contact us through our website 5sterrenalgoritmes.nl and share your questions and ideas!

References

-

See: https://english.rekenkamer.nl/publications/reports/2021/01/26/understanding-algorithms ↩

-

See: https://english.rekenkamer.nl/publications/reports/2024/10/16/focus-on-ai-in-central-government ↩

-

See: https://kpmg.com/nl/nl/home/topics/digital-transformation/artificial-intelligence/algoritme-vertrouwensmonitor.html (in Dutch) ↩

-

For example, the European AI Act (Art. 13) states that high-risk systems should be ‘designed and developed in such a way that their operation is sufficiently transparent to enable users to interpret, and use appropriately, their results’. Transparency also plays a prominent role in the Implementation Framework for the Responsible Use of Algorithms (Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations). ↩

-

Walmsley, J. Artificial intelligence and the value of transparency. AI & Soc 36, 585–595 (2021). ↩

-

As of 29 November 2024, there are 609 published algorithms, 430 of which come from municipalities, 21 from ministries, 36 from independent administrative bodies (usually executive agencies), and 17 from provinces. ↩

-

Morley, J., Kinsey, L., Elhalal, A., Garcia, F., Ziosi, M., & Floridi, L. (2023). Operationalising AI ethics: barriers, enablers and next steps. AI & SOCIETY, 1-13. ↩

-

Article 13.3 GIBIT 2023 procurement terms and conditions. See: https://vng.nl/sites/default/files/2024-10/gibit-articles-2023-en.pdf. See also the notes to Art. 13 of these procurement terms, p. 27, available here: https://vng.nl/sites/default/files/2023-12/vng_gibit_2023_toelichting.pdf (in Dutch). ↩

-

Jennifer Cobbe, Michael Veale, and Jatinder Singh. 2023. Understanding accountability in algorithmic supply chains. In 2023 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAccT ’23), June 12–15, 2023, Chicago, IL, USA. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 12 pages. https://doi.org/10. 1145/3593013.3594073 ↩

-

See: https://www.mensenrechten.nl/actueel/toegelicht/toegelicht/2022/aanhoudend-foutief-gebruik-algoritmes-door-overheden-vraagt-om-bindende-discriminatietoets (in Dutch) ↩

-

See: https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/kamerstukken/2023/07/06/antwoord-op-schriftelijke-vragen-bevindingen-onderzoek-duo-naar-fraude-met-studiefinanciering (in Dutch) ↩

-

See: https://english.rekenkamer.nl/publications/reports/2024/10/16/focus-on-ai-in-central-government ↩

-

See: https://publications.tno.nl/publication/34642601/SASNc3ZW/TNO-2024-R11005.pdf (in Dutch) ↩

-

See: https://www.autoriteitpersoonsgegevens.nl/en/themes/algorithms-ai ↩

-

See: https://www.raadvanstate.nl/publish/library/13/digitalisering_wetgeving_en_bestuursrechtspraak.pdf (in Dutch) ↩

-

See: https://publicaties.mensenrechten.nl/file/1405c7ee-821e-29f1-6d06-58971cf25a3d.pdf (in Dutch) ↩

-

See: https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/rapporten/2022/12/05/inrichting-algoritmetoezicht and https://magazines.rdi.nl/staatvandeether/2021/01/toezicht-op-ai-inspecties-delen-kennis (both in Dutch) ↩

-

Such as the Z-Inspection method, which is already being experimented with in the government. ↩

-

See: https://www.tno.nl/en/technology-science/technologies/synthetic-data-secure-learning-from/ ↩

-

See: https://www.belastingdienst.nl/wps/wcm/connect/nl/toeslagen/content/hulpmiddel-proefberekening-toeslagen (in Dutch) ↩

-

See: https://vogcheck.justis.nl/ (in Dutch) ↩

-

Conceived by Margaret Mitchell, formerly an ethicist at Google: https://arxiv.org/abs/1810.03993 ↩

-

See: https://www.digitaleoverheid.nl/overzicht-van-alle-onderwerpen/open-source/beleid/ (in Dutch) ↩